Note: This article supersedes the earlier blogpost on the topic of Yoga. The material in that post has been deleted.

(A more detailed version of this will be incorporated in my upcoming book: Calendars of India; Theory and Practice)

The Panchanga (pañcāṅgam) is an almanac that is based on the traditional Indian system of timekeeping. It lists the five key attributes (properties) of each day in a tabulated form (pañcāṅgam means ‘having five limbs’). The five attributes listed for the day are: The vāra (the weekday), the tithi (the phase of the moon), the nakṣatra (the constellation the moon is in), the karaṇa (the half-phase of the moon) and the yoga.

The seven-day week is a comparatively new concept in India, neither the Vedas nor the Epics talking about it. The vedas have a concept of a ṣaḍaha. (a six-day period which is used extensively in sacrificial timekeeping). The concept of the seven-day week is, however, quite ancient in the Mesopotamian cultures. The weekdays are named after the seven planets (the Sun, the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn respectively). The week clearly is half a fortnight (which is the approximate period from a full moon [or a new moon] to the next.) There are some processes defined to figure out how each day got its name. We will not go into details here.

The use of the tithi or phase of the moon is very ancient indeed. The phases, or the changing size, of the moon is the most observable of the astronomical phenomena. The cycle of the phases (as an example, the cycle between one full moon and the next) could be seen to be around 29 to 30 days. The phase of the moon would wane from the full moon through the last quarter (half-moon during the waning phase), to the new moon, then wax through the first quarter (half-moon during the waxing phase) to the next full moon. The first 15 phases are called the dark fortnight and the second 15 phases are called the bright fortnight. Astronomically, a phase (tithi) of the moon is the period where the difference in the longitudes of the moon and the sun goes through 12°. The full moon is when the difference is exactly 180° and the new moon is when the difference is 0°. The tithis are numbered from 1 to 15 of the waxing phases and 1 to 15 of the waning phases. If the difference in longitude is between 0° and 12°, it is considered the first phase of the bright half; if it is between 12° and 24° it is called the second phase of the bright half; it it is between 180° and 192°, it is the first phase of the dark half and so on. The tithi at a particular time is what is indicated by the difference in longitude at that time.

The ancients of many cultures numbered their day based on the phase of the moon that day. A day would be marked as the number of the tithi at sunrise (there are other methods of reckoning the tithi of the day as well).

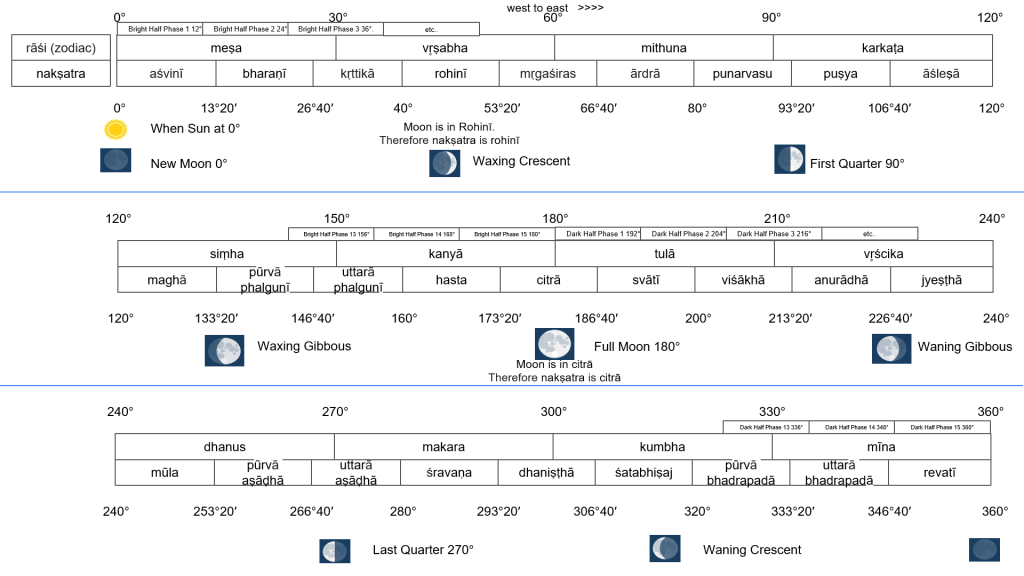

The nakṣatra at a particular time is the constellation the moon is in at that time. Our ancestors noted that the moon took approximately 27 days (plus a few hours) to go round the ecliptic. So, they divided the ecliptic into 27 constellations, each constellation having a width of 13° 20′ (=360°/27). Each constellation had a name (aśvinī up to revatī). So, if the moon’s longitude is between 0 and 13° 20′, it is said to be in the constellation of aśvinī, if between 13° 20′ and 26° 40′, then bharanī and so on. That is, divide the longitudinal difference by 13° 20′, and quotient plus one is the number of the nakṣatra at that time. A day is labelled as a particular nakṣatra if the moon is in that nakṣatra at sunrise (there are other methods of reckoning the nakṣatra of the day as well). Below is a figure showing the he nakṣatras and tithis. This shows where each phase (tithi) of the moon will occur when the sun is at 0° longitude.

We can see that when the sun is at 0° longitude (that is beginning of the nakṣatra aśvinī or the rāśi [zodiac sign] meṣa), the waning crescent happens at 45° longitude when the moon is in the nakṣatra rohinī. Similarly, the full moon happens when the moon is in citrā. Of course, the new moon happens when the moon is also at 0°. (As we said before, the nakṣatra at a particular time is the nakṣatra the moon is in at the time. Similarly, the rāśi [zodiac sign] at a particular time is the sign the sun is in at that moment.) It is easy to understand that when the sun is at say 40° longitude (that is the sun is in vr̥ṣabha), the phases get correspondingly shifted 40°.

(Note that in this picture we have assumed that the sun is stationary at 0°, while in actuality, the sun moves around 1° every day. So, by the time the moon goes from 0° back to 360°/ 0°, a period of around 27.3 days, the sun would have moved forward by around 27 degrees. Therefore, the next new moon will not happen at 0° but later at around that many degrees as the sun has moved over this time. This actually takes a little over 2 extra days. This is why the synodic period of the moon is 29.5 days [That is, though the moon goes round the earth in 27.3 days, the time taken from one new moon to the next or one full moon to the next is 29.5 days]

The nakṣatra and tithi are very ancient Indian concepts used from as far back as the Vedic period.

The karaṇa is half a tithi. It is the period of a six-degree (6°) difference between the longitudes of the moon and the sun.

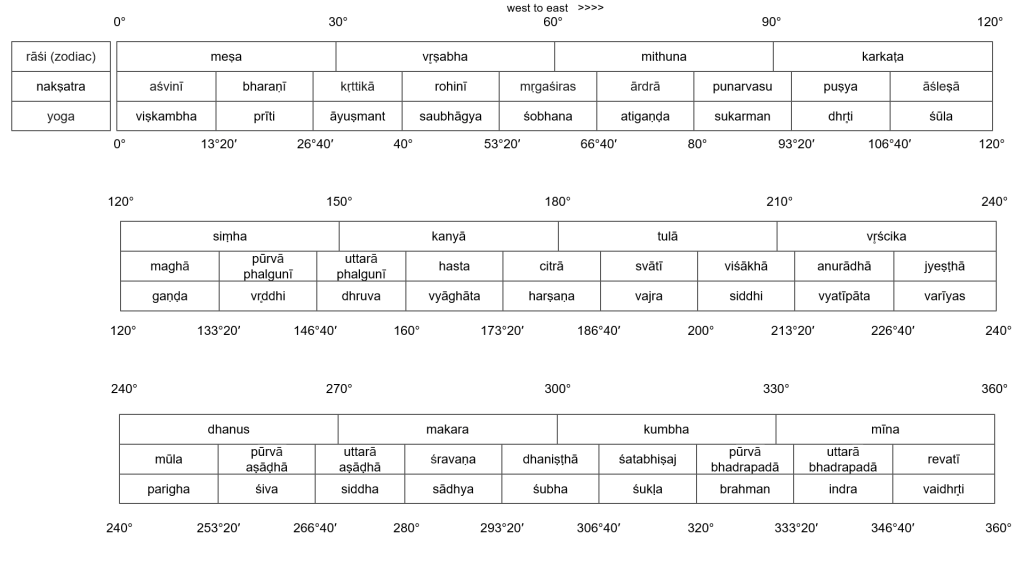

We now pass on to Yoga, which is the topic of this article. While the tithi at a particular time is reckoned as the difference between the longitudes of the moon and the sun at that time, the yoga at a particular time is the sum of the longitudes of the moon and the sun at that time. It is almost like a fictitious body having the longitude which is equal to the sum of the longitudes of the sun and the moon is moving through the zodiac. What is this thing called the Yoga? There are 27 yogas (like the nakṣatras). So, if the sum of the moon’s longitude and the sun’s longitude is between 0° and 13° 20′, it is said to be in the first yoga, if between 13° 20′ and 26° 40′, then it is in the second yoga and so on. That is, divide the longitudinal sum by 13° 20′, and quotient plus one is the number of the yoga at that time. These yogas, like the nakṣatras have names and the beginning and the end of the first yoga in the sky is the same as the beginning and end of the first nakṣatra and so on, since they both start at 0° and each have a width of 13° 20′. (The yoga is not mentioned in the Vedas etc. It seems to be a recent phenomenon that developed when astrology, as it is known now, became popular.)

What is the significance of it astronomically? While we are able to understand the astronomical significance of the other four angas of the panchanga, what is yoga? I have referred to many books and have not been able to find the answer.

In the figure below I have shown the ecliptic, or the path of the sun round the skies, with the zodiac and the nakṣatras and the yogas marked. You can see that the yoga boundaries are the same as that of the nakṣatra (constellation).

We said that the longitude of the fictitious body having the strength of the sun and the moon is the sum of the longitudes of the sun and the moon. Let us say that the sun is at 40°(vr̥ṣabha) and the moon is at 85° (punarvasu). The longitude of the fictitious combined body is then 40° + 85° = 125°. We can see that this falls within the yoga gaṇḍa. So, the yoga at that time is gaṇḍa. See picture below. (Note that the addition is modulo 360°. That is if the sum of the two longitudes is, say, 372°, it has to be reduced to [372-360 =] 12°).

The phenomenon is called ‘yoga’ meaning ‘junction’ or ‘conjunction’ because the yoga boundaries are the same as the nakṣatra boundaries. Remember that the main star of a nakṣatra is called a yogatarā or junction star. The yogatarā is used to identify the conjunctions of the planets (the moon, the sun etc.) with the nakṣatra (i.e. the position of the planet with respect to the nakṣatra), in the early days when observation was the main basis of the determination of the positions of the planets. When a planet was near the yogatarā, it is clear that the planet was in the corresponding nakṣatra.

Note that the Sūrya Siddhānta mentions the phenomenon of yoga in chapter 2 verse 65 only. My explanation above is of this verse. [I have used the translation and notes of Rev. E Burgess]

But interestingly chapter 11, which is of an astrological character, describes something that closely reminds us of the yogas. This chapter titled, Of Certain Malignant Aspects of the Sun and Moon, talks of when (the time at which) the sun and the moon have equal declination (north or south distance from the equator), they become malignant and cause ‘destruction of mortals’. Now, how is the time when the declinations are equal calculated?

If you add the longitudes of the sun and the moon (like for a yoga), when the sum is 180°, you can see that the declination is the same on the same side of the equator, and when the sum is 360°, the declination is the same, but of the opposite sides of the equator as shown in the figure.

Of course, the sum of the longitudes will behave as above only if we ignore the latitude of the moon and assume that both the sun and the moon move along the ecliptic. [In actuality, the moon’s orbit is inclined at 5.1° to the ecliptic, so corrections have to be made to figure out exactly when the declinations are equal. The Sūrya Siddhānta goes into this detail also.]

The Sūrya Siddhānta describes six aspects that are very malignant.

- When the sum of the longitudes is 360°, called a vaidhṛta or a vaidhṛti [which is the same as the name of the last yoga, where the sum of the longitudes is near 360°]

- When the sum of the longitudes is 180°, called a vyatīpāta [but note that the yoga where the sum of the longitudes is 180°, is called by some other name]

- However, the 17th yoga is called vyatīpāta, and coincidentally, the Sūrya Siddhānta in 11.20 says that when the sum of the longitudes of the sun and the moon is in the seventeenth nakṣatra (anurādhā), it is also a vyatīpāta

The Sūrya Siddhānta in 11.21 also talks of three other values of the sum of the longitudes which are also very malignant. This is when the sum of the longitudes is within a quarter of a nakṣatra length on either side of the endpoint of āśleṣā, jyeṣṭhā and revatī. [Note: the significance of the end of these three asterisms is that they coincide with the endpoints of the rāśis karkaṭa, vr̥ścika, and mīna. Why this fact of the coincidence of the endpoints of nakṣatra and rāśis should make them malignant is not known.]

In 1, 2 and 3 above we can see that there is a connection between the malignant positions of the sun and moon and the yogas.

To sum up, malignancy occurs

- whenever the declinations of the sun and moon are equal (either of the same side or opposite sides of the equator)

- when the sum of the longitudes of the sun and moon falls in anurādhā and

- when the sum of the longitudes of the sun and the moon fall within a quarter of a nakṣatra length on either side of the endpoints of āśleṣā, jyeṣṭhā and revatī.

So, it could be that the concept of yogas in astrology arose from the belief in this malignancy. [Of course, we are not sure why there is malignancy when the declinations of the sun and moon are equal]

But what is origin of the yoga? My theory is this:

The theory of malignancy described in the Sūrya Siddhānta must have been in circulation for a long time to have it included there. This theory of malignancy associated with certain combinations (sums) of the longitudes of the sun and the moon may have spawned a theory of the yogas mirroring the nakṣatras, assigning different results (malignancy, benignancy or neutrality) to all combinations (sums) of the longitudes of the sun and moon.

Both the karaṇa and the yoga have astrological significance. They are both used in the calculation of muhurtas (auspicious times for ceremonies like weddings). Days starting with certain karaṇas or yogas or times when certain karaṇas or yogas are running are avoided for doing any auspicious things.

[…] This article has been superseded by this blogpost – The Yoga in the Panchanga (pañcāṅgam) – An updated note […]